Clear as a friend's heart, 'twas, and seeming cool--

A crystal bowl whence skyey deeps looked up.

So might a god set down his drinking cup

Charged with a distillation of haut skies.

As famished horses, thrusting to the eyes

Parched muzzles, take a long-south water-hole,

Hugh plunged his head into the brimming bowl

as though to share the joy with every sense.

And lo, the tang of that wide insolence

Of sky and plain was acrid in the draught!

How ripplingly the lying water laughed!

How like fine sentiment the mirrored sky

Won credence for a sin of alkali!

So with false friends.

Pretend this is Lit 101. What on earth is going on in what I just read?

If you know some history you might have a leg up. This parched soul is named Hugh, and he's alone and in tough shape. If you remember the violence of The Revenant, your nightmares might just lead you to think "Hugh" is the bear-torn hero of that movie. He is.

But the rest of the class may need some background.

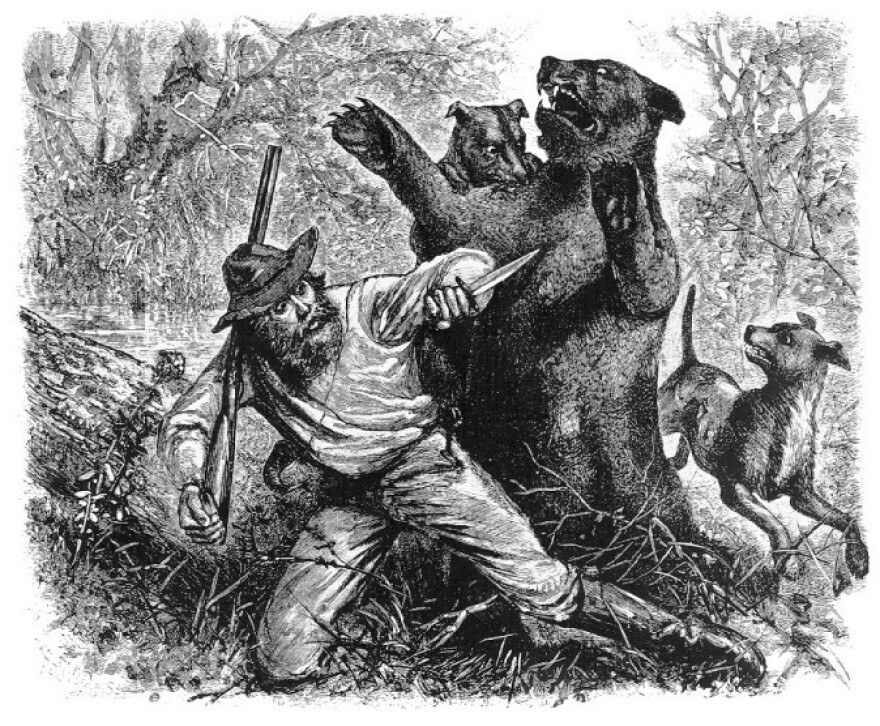

Hugh Glass has been left for dead. If you saw The Revenant or read the novel or read Lord Grizzily, by Frederick Manfred, you know the story of Hugh Glass, beaver trapper, circa 1830, left for dead after being mauled by a she-bear.

In the odd poem I just read, Hugh Glass is really thirsty; but what's with those "parched muzzles. . .thrusting"? And what kind of "lying water laughed" anyway?--and "ripplingly"? Seriously? "The sin of alkali" does a ton more than suggest that the crystal bowl so long-sought (Oh my goodness, I'm picking it up myself) turns out to be "acrid in the draught!" It ain't good--that's for sure. But isn't the whole thing a little ridiculous?

"The Song of Hugh Glass" is an ancestor to Manfred's Hugh, as well as Punke's and Leonardo DiCaprio's. What we're reading is the verse of John Neihardt, who was once himself a legend in Nebraska, and left a state monument in Bancroft. Neihardt penned his version of the Hugh Glass saga in an epic poem that sounds for all the world like Shakespeare or John Milton. That's a long haul from Bancroft.

When Neihardt took Lit 101, what he learned was that true literary stardom, a readership across the ages, needed to be penned in something called epic poetry. Think Homer--The Iliad and Odyssey. Maybe Beowolf?

So right out here in our backyard, John Neihardt figured the Hugh Glass story was just as great as any big legend—and just as central to a nation's identity.

"Why not?" Neihardt must have told himself. What America needs is its own Epic of Gilgamesh or Divine Comedy. Why not start with a wilderness man like Hugh Glass?

You got to love the aspiration, don't you? John Neihardt argued for world-class heroism right here on the Plains.

Plunged deeper than the seats of hate and grief,

He gazed about for aught that might deny

Such baseness: saw the non-committal sky,

The prairie apathetic in a shroud,

The bland complacence of a vagrant cloud--

World-wide connivance.

Amazing. In his dire hunger and thirst, Glass looks to nature for sweet solace and gets "the prairie apathetic" and a "vagrant cloud” because, dang it!—it seems to him that no one cares.

Okay, let's be blunt. A full century after Neihardt wrote the Hugh Glass story in Shakespearean English, it seems dead wrong, doesn't it?

Maybe. But you got to love Neihardt the bard. What he was doing was something we may well need more of--cheerleading. Neihardt believed our stories ranked with anyone's anywhere in time and space.

And he was right. Last year, The Revenant was awarded three Oscars. Wasn't the same Hugh Glass saga, wasn't set in Siouxland; but Neihardt was without a doubt on to something when he sang "The Song of Hugh Glass," something that began here, a story first written in Siouxland.