'Twas in the moon of winter-time

When all the birds had fled,

That mighty Gitchi Manitou Sent

angel choirs instead;

Before their light the stars grew dim,

And wandering hunters heard the hymn:

"Jesus your King is born, Jesus is born,

In excelsis gloria.

It's Christmas all right, “the moon of wintertime,” but this near 400-year old

French Canadian carol is a long way from the hills around Bethlehem. Gitchi

Manitou? "wandering hunters?" We’re nowhere near Luke 2.

Within a lodge of broken bark

The tender Babe was found, A ragged robe of rabbit skin

Enwrapp'd His beauty round;

But as the hunter braves drew nigh,

The angel song rang loud and high...

"Jesus your King is born, Jesus is born,

In excelsis gloria."

A bark lodge is the lowly stable, swaddling clothes have become rabbit skins, and

shepherds are "hunter braves."

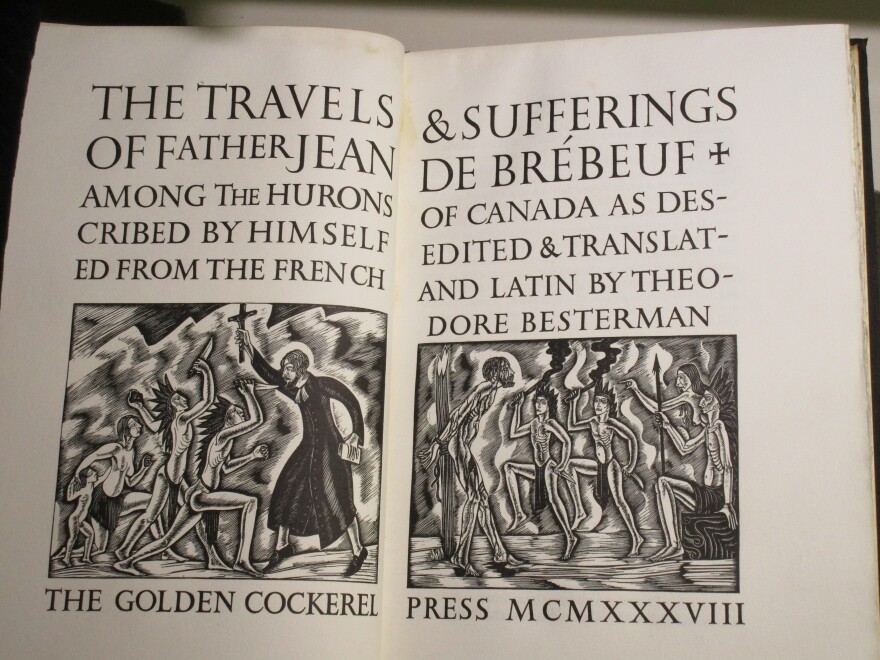

"The Huron Carol,” the very first North American Christmas carol, is almost as old as the boot prints on Plymouth Rock. It predates the American Revolution by more than a century and was written and sung in the Huron language by a man some still call Canada's "patron saint," Father Jean de Brébeuf, a French-Canadian Jesuit.

I read about it, and him, in a publication of the Hymn Society in the United States and Canada, a booklet titled Hymn Texts in the Aboriginal Languages of Canada (1992), from a series edited by someone I knew—Bert Polman. Hymn Texts was sent to me by someone who thought I’d appreciate it—and I did.

As enchanting as it is beautiful, the old carol creates a quiet nativity fully furnished as Native American, “Silent Night” in beaded moccasins. Ancient as it is, “The Huron Carol, in a delightfully disarming way, plays fast-and-loose with the gospel. I’m not sure my mother would like it.

Father Brébeuf, a towering presence, worked hard to learn the Huron language and even picked up the rhetorical earmarks of the people he came to serve. Then or now, mission work was no picnic; for years, the only Huron he baptized were at death’s portal. But Father Brébeuf, a powerhouse, was persistent, driven by what he considered his divine calling, so driven, in fact, that it cost him his life.

In March of 1649, he was accosted by the Iroquois, who were then battling the Huron. The Iroquois mocked his religion by baptizing him with boiling water, then finished an all-day ritual torture with a singular horror meant, strangely enough, to honor the black robe they'd slowly butchered: each of the Iroquois braves ate from Father Brébeuf's heart, hoping to share thereby the bravery and courage he had exhibited so unflinchingly before death took him.

If you know that story, it's difficult to hear “The Huron Carol” without recounting Father Brébeuf's life--and tragic death. The path the old hymn takes resounds with the man’s loving commitment to the Indigenous, who were, after all, the first to sing the Huron Carol, the men and women who slowly came to love him dearly. His desire was to show the light of the world to those he saw in darkness, to share with them the peace, he might have said, “that passeth understanding.”

Today, some claim Father Jean de Brébeuf was among the very first colonizers, on a mission to begin the cultural genocide of the Indigenous he claimed he came to save. The Huron had their own religion, their own way of life. No one asked a French priest to come around and change their world.

It's difficult not to hear the colonizer in the hymn Brébeuf created, the story he wanted so badly to craft in order to tell the Huron the Christmas story. He wanted the tiny baby in rabbit skins, their own Gitchi Manitou.

I just don’t know what to say about “The Huron Carol.” I’m quite sure I know some people who would spite the old hymn for its almost darling falsehoods--an Indian Jesus born in French Canada? Really?

Others will despise it for reeking of rapacious colonialism and its inherent racism.

“The Huron Carol” may be the oldest North American Christmas carol, but you probably won't hear it in Wal-Mart this season. Its well-meant baggage is certain to offend dignity and cancel someone’s culture. Father Brébeuf’s thoughtful hymn is difficult to talk about, and difficult to write about--believe me.

Some of you, I hope, will forgive me for saying it shouldn't not be played or sung or loved. “The Huron Carol” is a nearly 400-year-old Christmas hymn that not only tells an unforgettably complex story but is one. Its concerns today are ours—it’s undercurrents, its subtext on the nature of missions make any performance as much about us as it is the baby Jesus.

There’s nothing cute, nothing tinsel about it. Its tender loveliness and its blessed regards carry with it a very complicated peace that, as the Bible explains, passeth understanding.

If you’ve never heard it, take the time, just this once, this Christmas.